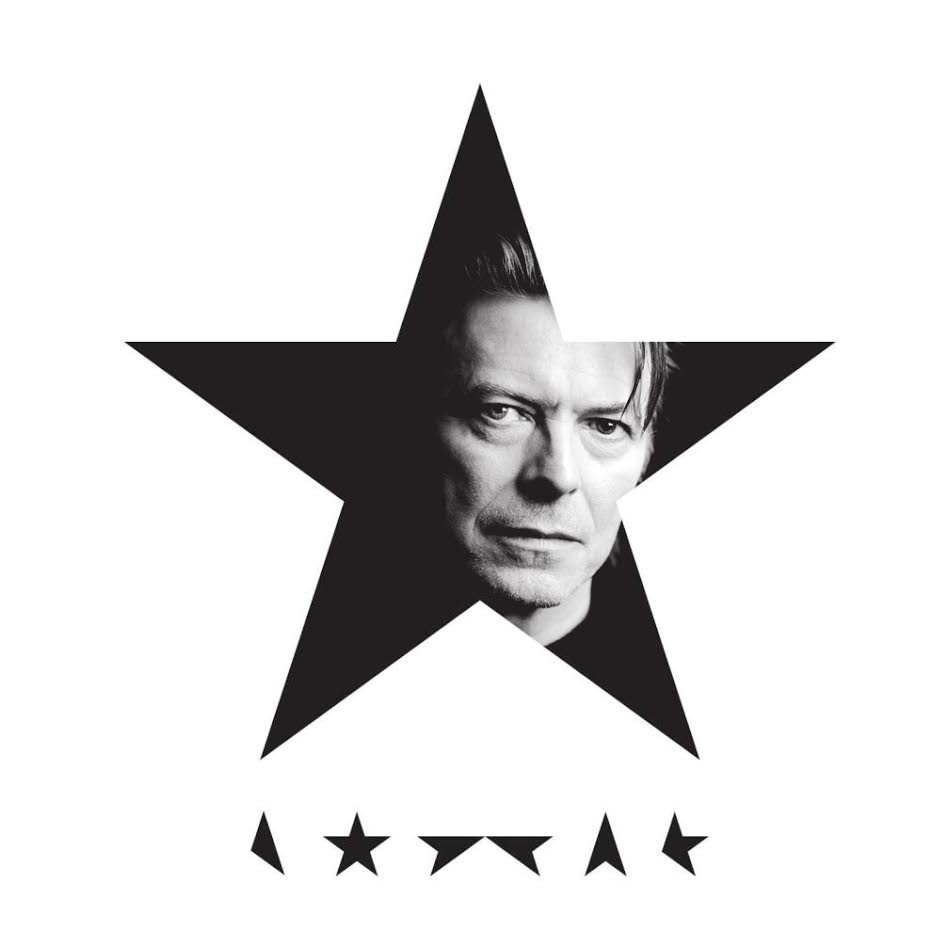

David Bowie, the supernova

The original article can be viewed here : http://www.theguardian.com/music/2016/jan/15/david-bowies-last-days-an-18-month-burst-of-creativity

For more than a decade before his death David Bowie seemed to disappear. Beset by ill health after an on-stage heart attack in 2004, he largely withdrew into a life at home in New York, becoming a ghost in the city where he had lived for a quarter of a century.

Yet as the world comes to terms with his death this week, admirers are digesting a remarkable late burst of creativity, a dramatic 18-month flourish capped by an apparently exquisitely well-crafted exit.

At 69, Bowie reasserted himself both as a musician – Blackstar, the album released two days before his death, is topping charts around the world – and as a questing creative figure whose vision is still playing out on the New York theatre stage.

How did Bowie pull this off from the penthouse duplex he shared with wife, Iman, and 15-year-old daughter, Lexi, in the Nolita section of downtown Manhattan?

The singer’s encroaching frailty meant he kept his life local. The theatre where his play Lazarus is running is no more than a few minutes walk away; Magic Shop, the studio where he recorded albums Blackstar and The Next Day, is even closer, on Crosby Street.

Magic Shop recording studio in Manhattan where David Bowie recorded Blackstar Photograph: Hannes Bieger

Each place would offer Bowie a last opportunity to work in the musical and theatrical worlds that he had specialised in amalgamating throughout his career. “He wasn’t any single thing,” longtime collaborator Mick Rock told the Guardian. “He was the great synthesizer.”

The picture that has emerged over the past few days is of a man who was able to shake off late career doldrums and, in spite of declining health, find a final, focused burst of creativity.

First, in 2013, came The Next Day, an album that was a stylistic tour of his career; then the V&A’s David Bowie Is – an exhibit of 300 objects of Bowie memorabilia revealing the consideration with which he had preserved the artefacts of his career; the play Lazarus, now set for London’s West End; and finally Blackstar, a jazz record that launched with a video that appears to anticipate his death.

According to Bowie’s longtime producer Tony Visconti, Bowie had known since at least November that his cancer was terminal. But even in his final weeks, Bowie had no idea how little time was left and was talking about a Blackstar follow-up.

Pictures from the opening night of Lazarus on 7 December last year showed Bowie still handsome and immaculate but possibly showing signs that he may have been unwell. Theatre producer Robert Fox, who worked with him on Lazarus, said Bowie never complained.

“The work was great and working with him was wonderful but it wasn’t great that he wasn’t well. It was not good at all. Some days he just wasn’t able to be around, but whenever he could be, it [his cancer] didn’t interfere with his contribution. It was just horrible for him, rather than difficult for us.”

Fox believed the work was not specifically coloured by Bowie’s sense of his own mortality. “The struggle with mortality goes on whether or not you’re unwell. People write about that stuff even when they’re in perfectly good health,” he said. But Fox, who helped Bowie find a director and cast the actors, concedes it must have had some effect.

“He would talk about his illness only to the extent that it affected his work. Not in any other way. He never grumbled. But I don’t think he planned on not being around. He was optimistic that something (a treatment) would come along that meant that he could be.”

David Bowie arrives at the premiere of the musical Lazarus. Photograph: BR/ dana press/PA

Bowie had been battling cancer for six months when he entered Magic Shop’s expansive studio facilities in January 2015 to record his 25th album. The studio, which has also been used by Coldplay and Arcade Fire, was already known to him; he had recorded much of his previous album The Next Day there. But instead of rock musicians, he brought seven demos to progressive jazz saxophonist Donny McCaslin.

The sessions were short and light-hearted, typically running from 11am to 4pm over three sessions of a week through to March. James Murphy of LCD Soundsystem came in to add synths and percussion and the tracks were finished off in Visconti’s own studio in April.

Visconti, who produced the album over the first few months of 2015, told Rolling Stone that Bowie showed up for some Blackstar sessions without eyebrows or hair after undergoing chemotherapy.

“There was no way he could keep it a secret from the band,” he told the magazine. “But he told me privately and I really got choked up when we sat face to face talking about it.”

Bowie’s affliction had not dulled his enthusiasm for work. “His energy was that of a very young person diving into everything with fearless joy and abandon,” said recent Bowie collaborator Maria Schneider, the orchestral-jazz composer. “Not to say he wasn’t serious. He was very clear about what he did and didn’t like.”

Annie-B Parson, of New York’s Big Dance Theater company, was the choreographer on the Lazarus musical and worked in close proximity with Bowie from September until the opening night in December.

She said she did not know he was ill and did not think the actors knew either as they worked quickly to develop the show in a tiny studio at the New York Theater Workshop.

But the director of the musical, Ivo van Hove, told her something that she only now realises the significance of. “At the beginning, he said this was the saddest piece he had ever worked on,” she said. “It’s deeply connected to death and a person contemplating his own existence from the first moment we see him.”

During rehearsals, Bowie sat quietly, elegantly dressed in grey sweater and white shirt, writing with a stub of pencil on a piece of paper. Physically, “all criss-crossed”, the choreographer noted, his slender arms and legs twisted about each other in concentration. Bowie would not intervene, but the creative team would get feedback.

“He insisted on spectacle. What struck me was that Bowie was from some other place, he wasn’t of this planet and he was cool with that,” Parson said.

It only occurred to her with hindsight that a person’s knowledge that they may have limited time left might fuel their creativity. Bowie was suddenly prolific, driven. “There was almost an insistence that he had so much to say. He needed to get out these songs in time. And he did,” she said.

Speaking on Friday from Warsaw, van Hove said: “The first thing that struck me when I met in a room in New York with David and Enda [Walsh, Bowie’s co-writer on the piece] and they read it to me and played some of the music was the existential theme – life and death and is there life after death or can you go on living just in your mind or your imagination?”

When Bowie told van Hove, in strictest confidence, in November 2014, that he had cancer and might not survive the project, the songs he was writing became deeper, especially Lazarus, the song of the eponymous musical and single.

“It is like his testament,” said van Hove.

Bowie’s creative surge was stunning. When he was feeling ill after treatment, he would stay away from rehearsals, but was intimately involved when in attendance and a genuine collaborator who thrived off his cohorts’ ideas, van Hove said.

“He was private about the details of his health situation. I didn’t question him, but I knew he did not want to die. He was in a struggle for life during those 18 months,” he said.

Some of the songs in the musical convey huge inner rage and a protest about violence in society, overlaid with poetry and layers of sound. “But in person he was always the perfect gentleman,” van Hove said. As Bowie became sicker, later in 2015, van Hove said he saw fear in his eyes. “He was fragile,” he said.

Sophia Anne Caruso and Michael C Hall in a scene from David Bowie and Enda Walsh’’s “Lazarus. Photograph: Jan Versweyveld/AP

After the opening night of Lazarus, Bowie had to sit down backstage with van Hove and Iman, exhausted after taking his bow. “I escorted him to his car and I somehow knew it was the last time I would see him.”

Music video director Johan Renck was already thrilled to be working with his childhood hero last July on the title track of the diamond heist TV drama The Last Panthers that he had directed in England, when the British pop icon told him there was more to the tune they had just recorded. A lot more – a version that turned out to be Blackstar, the towering single from the album Bowie had been writing.

“I flew from London to New York and met with him at his office in Soho to listen to the full track. He put his hand on my shoulder and said with a grin – ‘I must warn you, it’s 10 minutes long’. There was no way I could say no. He had this warmth and this infectious smile and I knew it would be an interesting journey,” Renck said.

The two began a fiercely intense and, as it turned out, all too short collaboration.

“Over Skype he said ‘I feel I have to tell you this. I’m very ill and I may not make it’. I had been in this playful mood, pitching ideas back and forth with him like giddy 12-year-olds and I was absolutely shocked. He said: ‘I don’t even know if by the time we shoot this video you will have to have a replacement for me to perform in it’,” Renck said.

Bowie gave Renck no details of his cancer, only that he would be in cycles of treatment that meant he would have “my good periods and bad periods”, the director said. Bowie asked Renck not to tell a soul – this is the first time he has spoken publicly since Bowie’s death.

When Bowie and Renck came to shoot the video for Blackstar in September and, in November, the next single Lazarus, the mood was exuberant.

They shot Bowie performing for one day for each video and just five hours on those days in a studio in Brooklyn. That was all his health would take, Renck said.

Bowie wanted it to feature an isolated village, then Renck came up with the idea of rituals that mixed the occult with a celebration of life. Bowie also wanted a scarecrow in the video, Renck said, and sent Renck his sketch for the macabre character Button Eyes that he plays in both videos. The sketch showed a bandaged head, buttons for eyes and just a small strip of a Mohawk for hair.

“Bowie didn’t know if he would have hair left by the time of the shoot,” said Renck.

In fact he did, a splendid shock of silvery grey hair – though he had to be careful or it came out in tufts because of his cancer treatment.

Unlike the sweeping anthem Blackstar, Renck described Lazarus as a little gem. Bowie reappears as Button Eyes, tormented on a hospital bed.

“I just thought of it as the Biblical tale of Lazarus rising from the bed. In hindsight, he obviously saw it as the tale of a person in his last nights,” said Renck.

While working, Bowie talked of his family but kept himself quite private, while being very easygoing and friendly with the small crew that worked on the intimate shoot.

He would arrive so suave in suit and fedora and sip cups of tea, Renck said, Despite the warning, he did not realise the star was so gravely ill because he seemed so spritely while shooting. He would get tired and take breaks, Renck said, but he seemed so happy.

The video of Lazarus shows Button Eyes and also Bowie’s other “character”, a dancer in a slick suit, gyrating in classic Bowie camp style then writing frenetically, a man desperately running out of time. Finally the figure retreats into a wardrobe and shuts the doors behind him.

It’s haunting but also witty, mocking death, Renck said.

“So British, the wit, like a guilt thing, making sure it’s not coming across as too serious or pretentious – and yet that enhances the humanity of it.”

Renck and Bowie also agreed that the joke was that the star, legendary for his gender-bending and fluid sexuality, was going “back into the closet”.

“The closet, or coffin, if you will,” said Renck.

A découvrir aussi

- House of Love - New album IS OUT NOW !

- Black Swan Lane - New album - Out now

- Black Swan Lane - The new album is out now !

Inscrivez-vous au blog

Soyez prévenu par email des prochaines mises à jour

Rejoignez les 18 autres membres